The

Humanities’ Lens

on

Racism

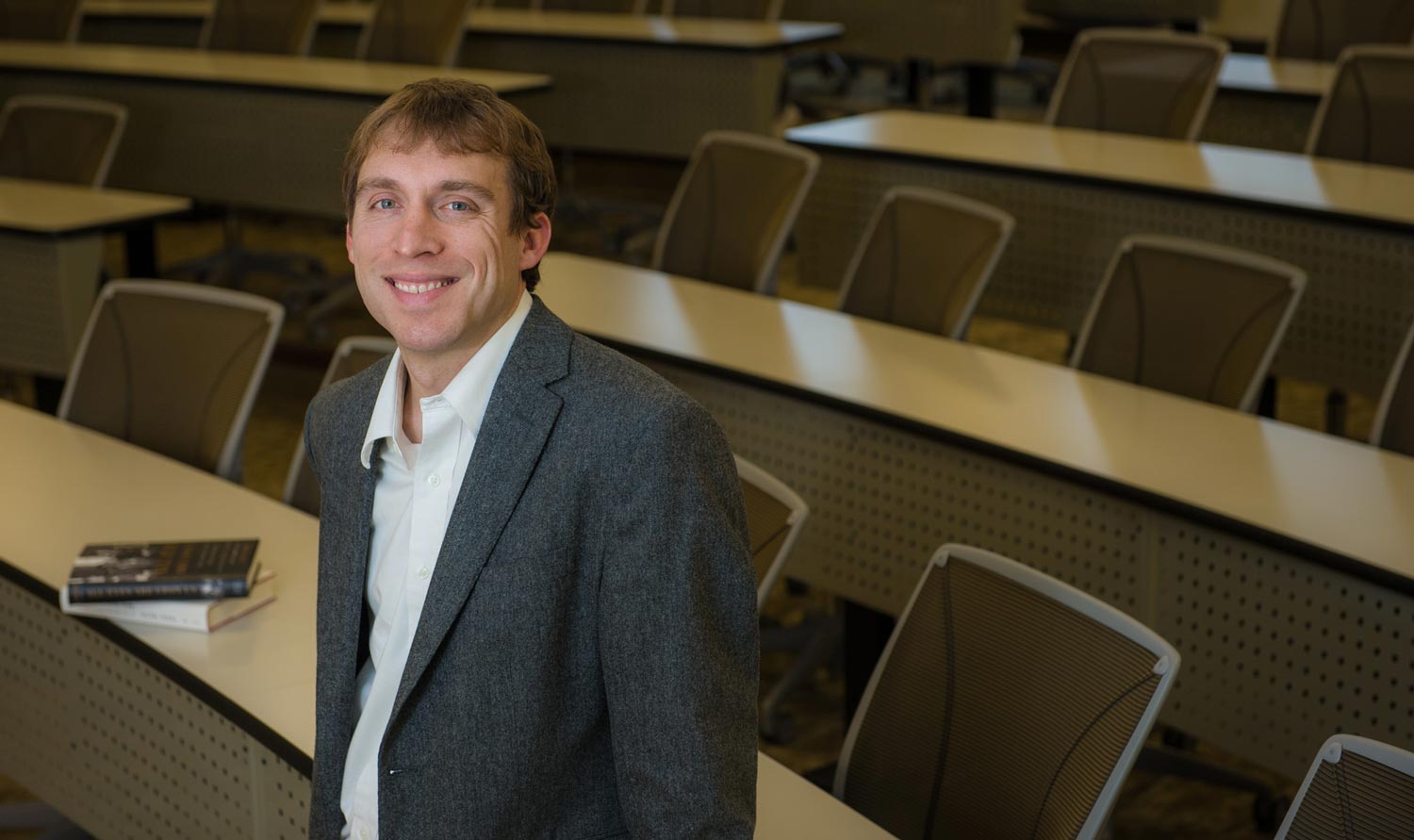

By digging into the humanities and social sciences, UNH faculty members tackle the history of racism throughout the world and how we can learn from it to respond to our present moment of racial reckoning. Through their scholarship, faculty are able to provide broader context related to what’s happening today, says Michele Dillon, dean of the College of Liberal Arts (COLA).

Photo by Jeremy Gasowski

Baumgartner is now writing a book that studies the life and activism of Robert Morris, a largely unknown African American lawyer and activist who practiced in 1850s Boston. Morris’s papers provide insights into his racial justice work related to education, labor, abolition and the rights of fugitive slaves. That fact that most people aren’t familiar with his work shouldn’t surprise us, Baumgartner says.

“Scholars have argued that white New Englanders tried to bury slavery and the contributions of African Americans to this region in order to differentiate New England from the South,” she explains. “As a scholar of Black New England history and culture, I’ve had to dig deeper into this history and find it. Many documents have been destroyed, misplaced or are difficult to locate.”

Although King is now canonized as a civil rights hero, he was initially seen as a polarizing figure, “scorned by many white Americans, worshipped by some African Americans and liberal whites, and deemed irrelevant by many Black youth,” Sokol writes. King’s legacy evolved after his death, although the book reveals that the deep divisions between Americans at the time of his death still exist today.

Dennis Britton, associate professor of English, is the author of “Becoming Christian: Race, Reformation, and Early Modern English Romance” (Fordham University Press, 2014). In it, he looks at the intersection of race and religion, arguing that the post-reformation English church developed a theology that created skepticism about the possibility of conversion if one was not born and baptized into the Christian religion.

“The ways in which Protestant theologians connected religious identity to race still manifest themselves today,” says Britton. “For example, those who believed President Obama was Muslim assumed he must have the same religious identity as his Black, African, Muslim father. Religious identity was assumed to be inherited in the same way that racial features like hair and skin color are.”

“This brings further attention to the research mission of UNH, and it’s another way to elevate attention to global racial issues,” she says.